Accession, War and the Seeds of an Endless Dispute

Recap: Princely States at the Crossroads

In the earlier chapter of the “India After 1947” series, we examined the daunting challenge that confronted India on the night of independence—the integration of 565 princely states. While most joined India or Pakistan readily, some like Bhopal, Travancore, Junagadh, and Hyderabad, resisted or tried to remain independent, creating dramatic clashes of ambition, diplomacy, and public revolt. Through negotiations, steadfast leadership, and sometimes direct military action, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V.P. Menon orchestrated the accession of hundreds of states, ultimately weaving together India’s fragmented political landscape.

We explored how Bhopal’s reluctant merger, Travancore’s reversal amid public unrest, Junagadh’s controversial flight to Pakistan, and Hyderabad’s intense internal conflict—all highlighted the complexities of building a united India. The saga concluded with Patel and Menon ensuring that, despite strife and resistance, the vast majority of princely kingdoms became part of the world’s largest democracy, setting the stage for a new nation forged in the fires of freedom and unity.

Introduction: Kashmir’s Distinct Destiny

Of all India’s princely states, Kashmir’s journey in 1947 stands out for its complexity, drama, and lasting global impact. As the British Raj faded, the Mountbatten Plan not only split the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, but also triggered a lapse of paramountcy—leaving 565 princely states to choose their fate. Most eventually merged with one of the two newly-created dominions, but a handful—Kashmir above all—set off a crisis that remains unresolved even decades later.

Kashmir’s difference lay in its demographics and its ruler. Where Bhopal, Junagadh, and Hyderabad saw Muslim rulers with Hindu-majority populations, Kashmir was ruled by a Hindu king (Maharaja Hari Singh) over a primarily Muslim population (77%). This fundamental tension shaped every decision and hesitation, making it nearly impossible for the state to commit to either India or Pakistan.

The End of Paramountcy — Choices and Uncertainties

On July 3rd, 1947, Lord Mountbatten announced the lapse of British paramountcy, giving each princely ruler the legal power to choose India, Pakistan, or even independence. While many states initially hoped to remain independent, reality proved fraught with danger and instability. Patel and V.P. Menon moved quickly to integrate most states through diplomacy or direct intervention. But Kashmir’s unique situation, with its strategic location, religious makeup, history of autonomy, and personal ambitions, confounded a simple resolution.

Maharaja Hari Singh wanted to preserve independence. He believed accession would risk revolt—either from his Muslim subjects (if he joined India) or from his own position as a Hindu ruler (if he joined Pakistan)

Standstill Agreements — Stalling for Survival

In this climate, Hari Singh offered standstill agreements to both India and Pakistan, hoping to maintain trade, transport, and essential supplies while avoiding a commitment. Pakistan agreed to the arrangement: India did not. The Maharaja’s hesitation thus left Kashmir vulnerable and isolated, while the state’s Muslims and Hindus grew anxious about their future.

Across the region, communal tensions simmered. Pakistan increasingly viewed Kashmir as a prize to be won—a “signed cheque” in Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s words, ready to be cashed at any moment.

Crisis Ignites: The Pakistani Tribal Invasion

By Mid October 1947, that moment arrived. Pakistani authorities, frustrated by Hari Singh’s indecision and seeking to force the outcome, launched an invasion using Pashtun tribal militias from the Northwest Frontier Province. These tribal “lashkars” believed they were liberating fellow Muslims, but quickly turned to brutality—looting, rape, murder—ravaging towns such as Baramulla and terrorizing the population. The Muslim revolt in Poonch and Mirpur had already erupted, with western Jammu districts falling out of the Maharaja’s control.

The tribes advanced to within 35 kilometers of Srinagar, the capital, and threatened complete occupation. Maharaja Hari Singh, in mortal fear, reportedly told his Diwan he would rather die sleeping than witness the fall of Kashmir.

Instrument of Accession: A Race Against Time

With Srinagar on the brink, Hari Singh fled to Jammu and appealed to India for urgent military help. India’s leaders—Nehru, Patel, and Menon—agreed but set a condition: the Maharaja had to sign the Instrument of Accession, formally merging Kashmir with India and granting Delhi control over defense, communications, and external affairs.

On October 26, 1947, the Maharaja signed the Instrument. V.P. Menon rushed the document to Delhi, and Indian forces prepared for intervention. A British plane famously airlifted troops to Srinagar airport, just as Pakistan-backed lashkars neared the city.

The Arrival of Indian Forces and Sheikh Abdullah’s Rise

On October 27, 1947, Indian Sikh battalions landed in Srinagar. Their arrival was a turning point. With the help of Sheikh Abdullah, a charismatic political leader recently freed from jail (and Nehru’s trusted confidant), Kashmiri resistance pushed the invaders back. The airport’s defense marked a dramatic moment—a close brush with disaster, but ultimately, a successful repulsion of the tribal advance. Srinagar and much of the Valley remained with India.

Sheikh Abdullah became a central figure. Descended from a Brahmin family and converted to Islam, he had founded the Muslim Conference (later renamed the National Conference) and advocated secularism, democracy, and integration with India. Nehru and Gandhi admired his politics and vision, betting that his leadership would legitimize accession in the eyes of Kashmir’s Muslims.

War Expands: The First Indo-Pakistani Conflict

With Indian troops in Kashmir, the conflict escalated:

- Pakistan’s regular army joined the lashkars, violating the “standstill” agreement.

- Indian forces, now supplied and coordinated from Delhi, fought to reclaim territory.

- In western Jammu and northern Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistani-supported uprisings led to the establishment of Azad Kashmir and eventual Pakistani control.

Fierce battles raged across mountains and valleys. Indian and Pakistani advances waxed and waned, solidifying the fronts along what became the Line of Control.

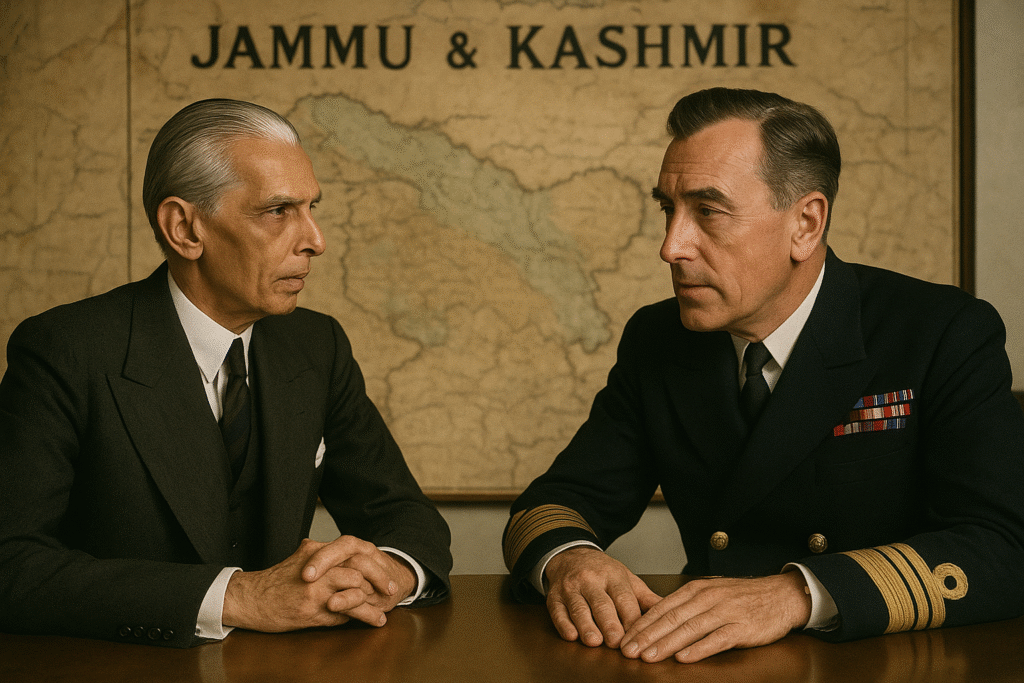

The Lahore Meeting: Jinnah and Mountbatten on Kashmir

As the Kashmir crisis escalated, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Viceroy of Pakistan) met Lord Mountbatten (Viceroy of India) in Lahore in a tense diplomatic encounter. Jinnah fiercely claimed that Pakistan had no control over the tribal militias invading Kashmir but insisted India’s Instrument of Accession was a “fraud” enforced by military means. He demanded Pakistan’s right over Kashmir, citing its Muslim majority.

Mountbatten firmly rebutted, accusing Pakistan of sponsoring aggression and insisted that Pakistani forces and militias must withdraw before any negotiations. He called for United Nations intervention to mediate impartially. Jinnah, however, insisted the plebiscite must be conducted only under the supervision of the Governor-Generals of India and Pakistan—himself and Mountbatten—rejecting UN involvement.

The meeting ended deadlocked, reflecting the deep political divide and setting the stage for prolonged conflict. Mountbatten’s firm stance and Jinnah’s refusal to compromise underscored why Kashmir remains the most contentious dispute in South Asia.

Internationalization: United Nations and the Plea for Arbitration

With fighting threatening regional stability, Nehru made a fateful decision—to take the Kashmir dispute to the United Nations (UN). Convinced that a plebiscite would demonstrate Kashmir’s support for India, Nehru agreed to international mediation and oversight. On January 1, 1949, the UN brokered a ceasefire and drew the Line of Control—the unofficial border that remains today.

The UN’s Resolution 47 required:

- Pakistan to withdraw its troops from Jammu & Kashmir

- India to reduce its military presence afterwards

- A plebiscite to determine Kashmir’s final status

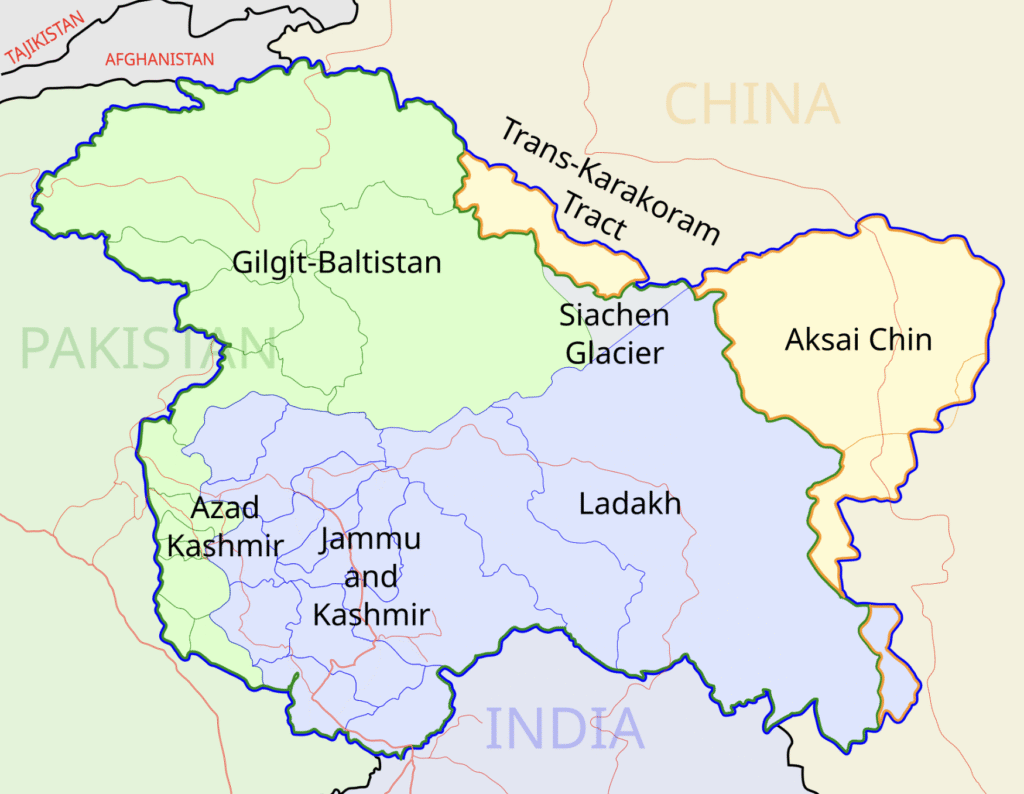

However, Pakistan never withdrew its forces. India, consequently, did not hold the plebiscite, and stalemate set in. Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan remained under Pakistani administration, while India retained Jammu, Ladakh, and the Kashmir Valley.

The Aftermath: Partition, Power, and Endless Dispute

Kashmir had become a divided land—India-controlled Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan-administered Azad Kashmir (POK) and Gilgit-Baltistan, and in later decades, portions occupied by China. Each region bore the scars of invasion, communal violence, and political uncertainty.

Sheikh Abdullah was made Prime Minister of Jammu & Kashmir in March 1948, marking a shift toward democratic governance. He aligned the state’s policies with Indian secularism, although tensions persisted between Abdullah’s party and pro-Pakistan voices.

In the weeks and months after accession, Nehru’s public speeches and radio broadcasts—often written with input from Patel—laid out India’s vision for Kashmir: secular democracy, inclusive government, and, when possible, peaceful coexistence with Pakistan.

Behind the Scenes: The Roles of Mountbatten, Menon, Patel, Nehru

Maharaja Hari Singh’s indecision was often shaped by persistent advice, warnings, and negotiations:

- Lord Mountbatten favoured Pakistan’s claim before partition, believing it would avoid unrest—yet he pressed for decisive action when tribal invasion loomed.

- V.P. Menon acted as a fixer, shuttling documents and diplomats, convincing Hari Singh to accede, and overseeing emergency measures.

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel advocated robust integration and security, often from behind the scenes, while giving Nehru the front seat for sensitive negotiations.

- Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to frame Kashmir in the light of India’s secular, democratic future—elevating Sheikh Abdullah as evidence of Muslim support for Indian unity.

Complexities of Loyalty, Ethnicity, and Realpolitik

Kashmir’s story is not just political—it’s deeply human:

- Muslim Conference, now National Conference fostered local power struggles.

- Muslim-majority districts in Poonch, Mirpur, and Gilgit region gravitated toward Pakistan.

- Hindu-majority areas in Jammu and Sikh communities in the east supported India.

The mass violence in Baramulla, Poonch, and surrounding districts remains one of the tragic reminders of how lives and destinies are shaped by sudden decisions and historic inertia.

Kashmir and the “What-Ifs” of History

As the dust settled, new questions arose:

- If Sardar Patel had led the accession process, would all of Kashmir have become part of India—like Junagadh and Hyderabad?

- If Nehru hadn’t announced UN intervention and a plebiscite, could India have consolidated control over the whole territory?

- Did the United States’ silent support for Pakistan at the United Nations foil India’s hopes?

- If Maharaja Hari Singh had decided sooner, could violence and division have been avoided?

These debates, grounded in personal letters, memoirs, and diplomatic exchanges, continue among historians, politicians, and ordinary citizens—even into 2025. Conclusion: Kashmir’s Legacy and Unfinished Chapter

Conclusion: Kashmir’s Legacy and Unfinished Chapter

Kashmir’s story after 1947 is a tapestry of hope, violence, betrayal, and resilience. It shows how history was shaped by unique personalities—kings, prime ministers, soldiers, and visionaries—operating in the shadows of empire and the glare of independence.

The unanswered questions and the unhealed wounds remind us that political decisions live long after they are made. Kashmir became not just a place on the map, but the focal point of lives, beliefs, and struggles that continue today.

Coming Next:

Blog 1.5: Drafting the Constitution: The Blueprint of Democracy, we will explore how India’s founding leaders came together to create the guiding framework of the nation — a visionary document that not only defined rights and duties but also laid the foundation for the world’s largest democracy.

References (Books):

1. The Story of the Integration of the Indian States– V.P. Menon (1956)

2. The Transfer of Power in India – V.P. Menon (1957)

3. Freedom at Midnight — Dominique Lapierre & Larry Collins (1975)

4. The Discovery of India — Jawaharlal Nehru (1946)

5. The Transfer of Power 1942–47 (12 Volumes) — Edited by Nicholas Mansergh

6. Patel: A Life – Rajmohan Gandhi (1990)

7. India After Gandhi – Ramachandra Guha (2007)

8. Looking Back- Mehr Chand Mahajan’s Autobiography (1963)

9. Karan Singh – Autobiography (1994)

References (TV Shows/Movies):

1. Pradhanmantri TV Series- ABP News (2013)

2. Freedom at Midnight- Sony Entertainment Television (2024)

References (Web Pages):

1.https://theleaflet.in/britain-had-no-option-but-to-grant-independence-to-india-on-august-15-1947/#:~:text=Finally%2C%20on%20February%2020%2C%201947%2C%20he%C2%A0announced%C2%A0the%20decision%20to%20grant%20independence

4.https://twitter.com/KulbeliTweets/status/1163513183245656064/photo/1

7.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North-West_Frontier_Province#/media/File:NWFP_(1901-1955)_map.gif

19.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/readersblog/insideoutside/instruments-of-accession-23183/#:~:text=Meanwhile%2C%20the%20rulers%20of%20the%20two%20states%20that%20were%20subject%20to%20the%20suzerainty%20of%20Junagarh%2DMangrol%20and%20Babariawad

20.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/readersblog/insideoutside/instruments-of-accession-23183/#:~:text=In%20response%20Nawab%20militarily%20occupied%20the%20states