Building the World’s Largest Democracy

Recap: Blog 1.5: Drafting the Constitution: The Blueprint of Democracy

Between 1946 and 1949, India’s leaders—Ambedkar, Prasad, Nehru, Munshi, and others—debated rights, governance, and federalism in the Constituent Assembly, producing the longest constitution in the world. Blog 1.5 explores their vision, the key compromises, and the process that led to the adoption of the Indian Constitution on January 26, 1950, shaping India’s democratic foundation.

Introduction

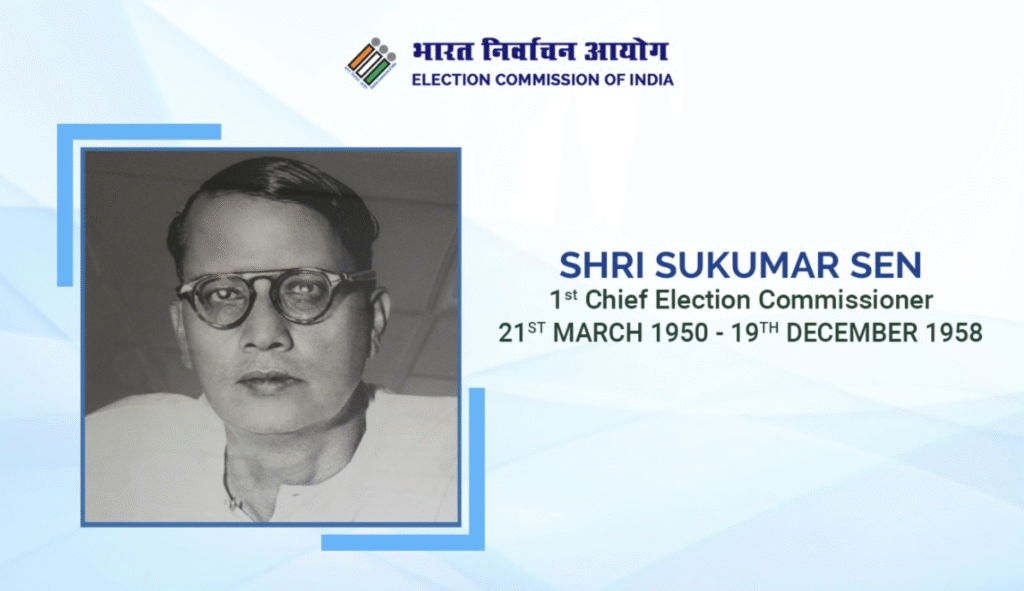

India’s first general election (1951–52) was a marvel of democratic achievement—an audacious experiment led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and the pioneering Election Commissioner Sukumar Sen. Despite a population that was mostly poor, illiterate, and unaccustomed to voting, the process enfranchised over 173 million adults—making India the first developing nation to adopt universal adult franchise at such scale.

Challenges and Triumphs

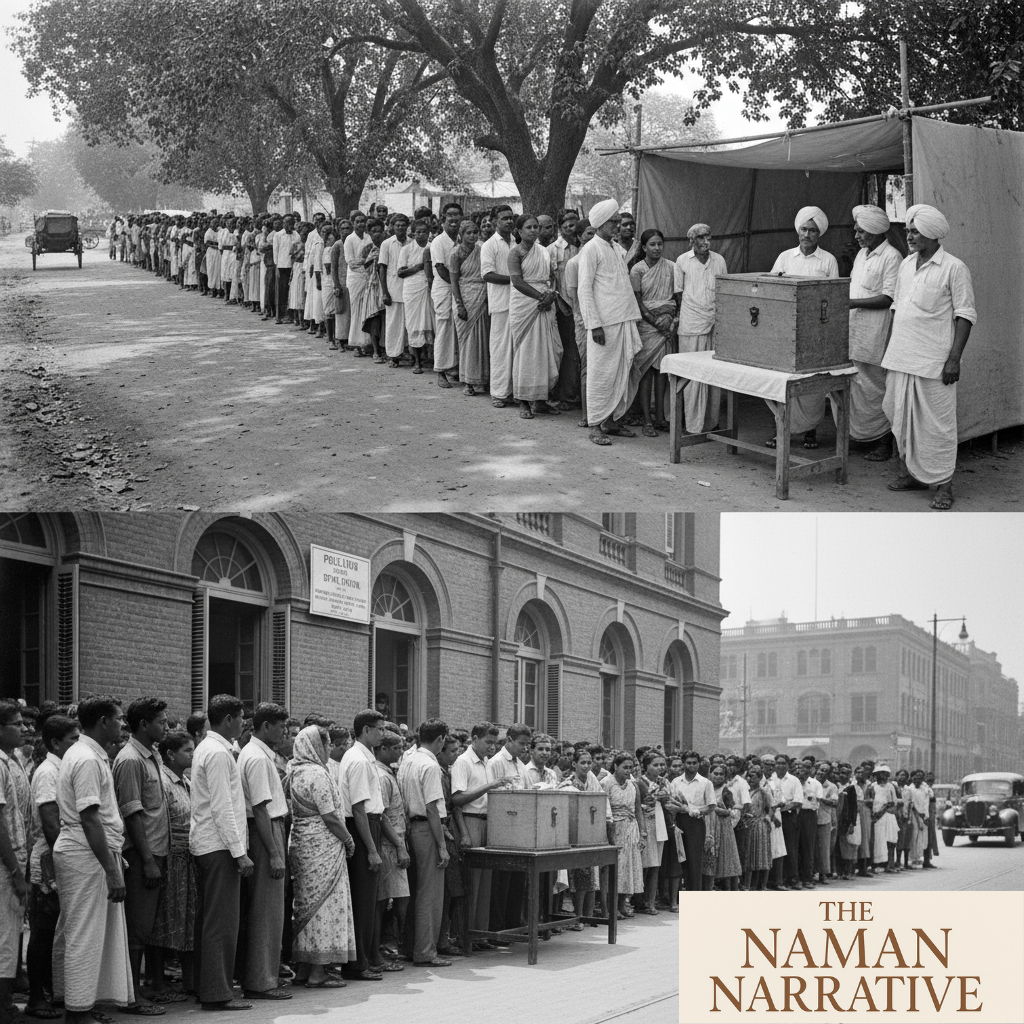

The logistical challenges were immense: an untrained populace, lack of existing rolls, difficulties in reaching remote villages, and widespread scepticism inside and outside the country. The Election Commission headed by Sen built the entire framework from scratch—registering voters, innovating with symbols for the illiterate, and spacing out polling over many months. The meticulous planning and education campaign made the voting accessible and orderly, evidenced by long queues, enthusiastic participation, and high voter turnout. US Ambassador Chester Bowles observed women, minorities, and rural citizens lining up alongside elites, redefining the idea of democracy for a new world.

Outside India, global skepticism gave way to admiration as the election’s success became clear. The British, still doubtful about Indian unity and stability, admitted that the “leap into democracy” had succeeded. Headlines in the Western press called it “history’s biggest free elections” and “a staggering success.” Even commentators in the US—fearful of leftist parties—had to acknowledge the stability and pluralism on display.

Political Change: Parties and Personalities

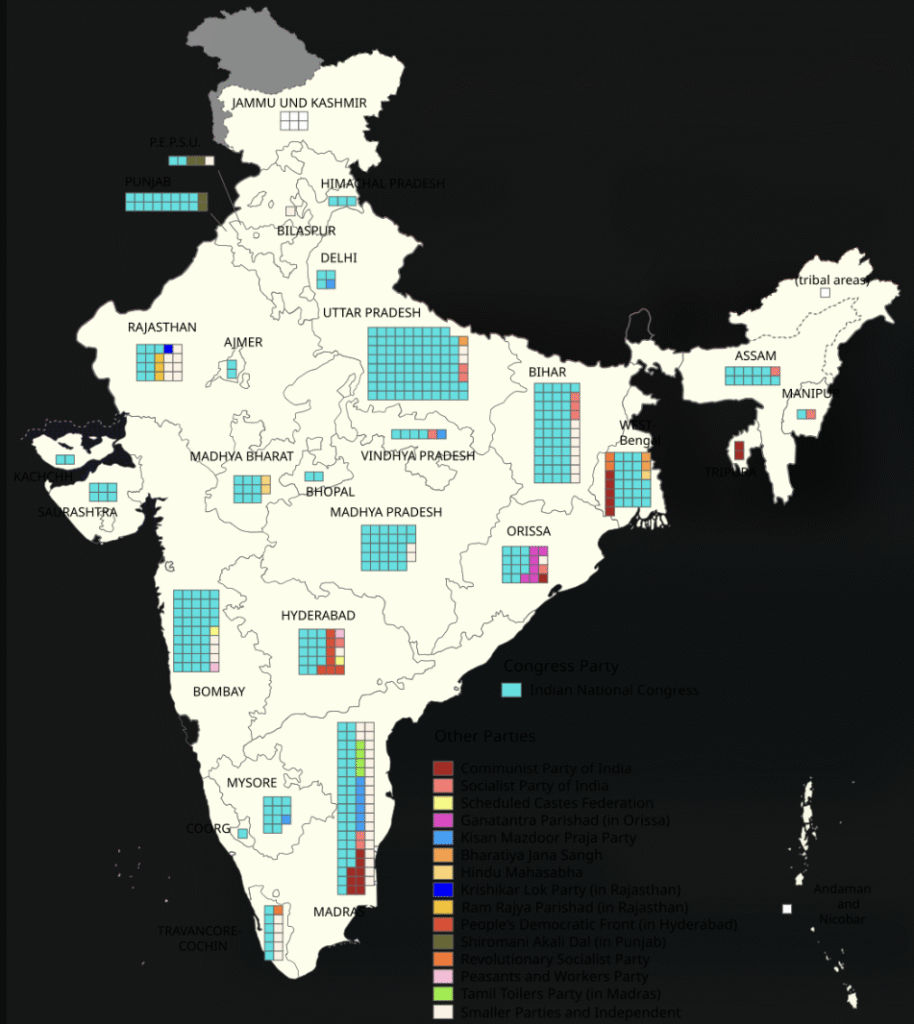

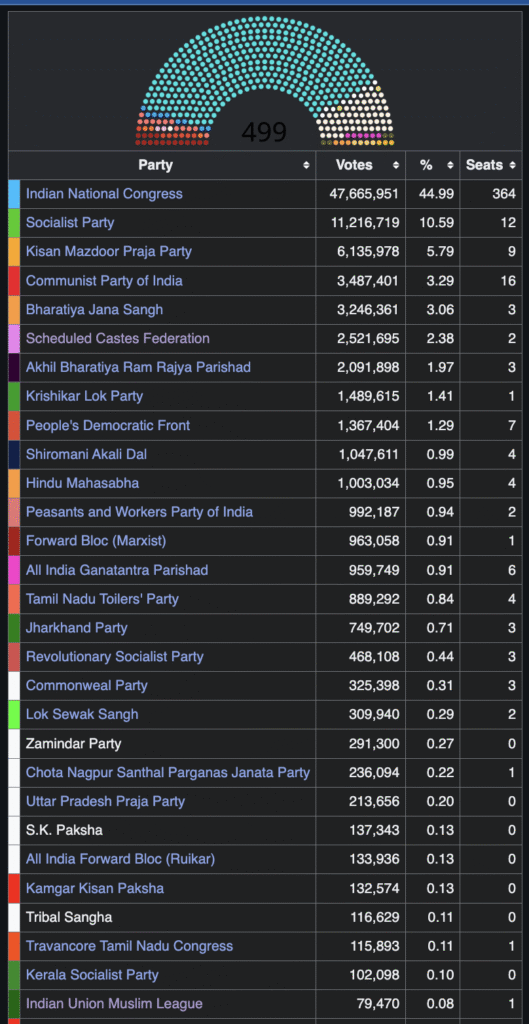

The 1952 poll marked the formal transition from resistance parties to electoral competition. The Indian National Congress (INC), led by Nehru, ran on unity, secularism, and development, and swept the polls with 364 of 489 seats. However, it was not uncontested. The election launched the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, founded in October 1951 by Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, as the first ideologically distinct opposition, championing cultural nationalism and criticizing minority politics. The Communist Party of India (CPI) and Socialist Party also gained ground, especially in the South and Bengal, and the Praja Socialist Party was formed from smaller socialist groups, soon emerging as a significant force in Kerala and Travancore.

The campaign trail featured spirited speeches from Nehru, Sucheta Kripalani, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Ram Manohar Lohia, and others, with rallies and local debates shaping India’s new political culture. New parties—Ganatantra Parishad and Scheduled Castes Federation—gave a say to erstwhile royals, marginalized groups, and minorities.

Princely States and Democratic Integration

By 1951, the political integration of princely states was complete. Most former rulers were now ceremonial heads or ordinary citizens; some contested as candidates, while unions like PEPSU became full-fledged states with elected governments. Rajpramukhs, once powerful kings, saw their influence replaced by constitutional office; even their privileges would be abolished within two decades. Resistance gave way to acceptance—India’s princes learned to compete not by birthright, but by ballot.

Nehru’s Vision: Policy and Social Change

The successful election vindicated Nehru’s democratic faith. The First Five-Year Plan (1951–1956), launched soon after, used electoral legitimacy to prioritize agriculture, dam construction, industry, health, and education. By winning a popular mandate, Nehru cemented the principle that economic planning must be accountable to the people, and that government policies were the servant of the electorate, not the arbitrary ruler.

Impact and Legacy

India’s first election became the foundation of its democratic destiny. In a nation of stark diversity—urban and rural, rich and poor, Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, and others—the peaceful, orderly conduct of the vote disproved colonial predictions of chaos or fragmentation. Political pluralism flourished: the Congress dominated, but opposition parties found legitimacy and new leaders emerged from grassroots activism.

By giving every adult a vote regardless of wealth, education, gender, caste, or previous royal status, India set itself apart: only four other countries offered universal adult franchise at the time, and none attempted it on such scale or with a population so varied.

International media marveled at the accomplishment. The New York Times reported the success as “an unprecedented experiment in democracy,” and Britain’s High Commissioner praised the “remarkable efficiency” and “discriminating use of the vote” by a largely illiterate population. Countries from Asia and Africa approached India to learn how such an organizational feat was possible.

Relevance Today: 2025 and Beyond

Seventy years later, this legacy resonates more than ever. With over 900 million registered voters today, every ballot cast is a testament to the immense vision of Nehru, Sukumar Sen, and others who believed in India’s capacity for democracy. Despite criticisms and challenges, India’s electoral system continues as the fulcrum of its democracy, ensuring peaceful transfer of power, holding governments accountable, fostering social change, and celebrating the rights of every citizen.

As debates about India’s democratic credentials persist, it’s worth remembering that in 1952, India proved—against all odds—that democracy was not just possible, but beautiful, bold, and enduring.

Conclusion:

At the close of this blog, the first phase of the “India After 1947” series—the Birth of a Nation—stands complete.

Starting next week, we will embark on the Phase 2: The Nehruvian Era and Early Challenges (1952-1964). The upcoming Blog 2.1 : The Hindu Civil Code, will explore the key social reforms amidst the political transformations of post-independence India.

References (Books):

1. The Story of the Integration of the Indian States– V.P. Menon (1956)

2. The Transfer of Power in India – V.P. Menon (1957)

3. Freedom at Midnight — Dominique Lapierre & Larry Collins (1975)

4. The Discovery of India — Jawaharlal Nehru (1946)

5. The Transfer of Power 1942–47 (12 Volumes) — Edited by Nicholas Mansergh

6. Patel: A Life – Rajmohan Gandhi (1990)

7. India After Gandhi – Ramachandra Guha (2007)

8. Waiting for a Visa – Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

9. Atmakatha – Dr. Rajendra Prasad

References (TV Shows/Movies):

1. Pradhanmantri TV Series- ABP News (2013)

2. Freedom at Midnight- Sony Entertainment Television (2024)

3. Samvidhaan: The Making of the Constitution of India – Rajya Sabha TV (2014)

References (Web Pages):

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1951%E2%80%9352_Indian_general_election

2. https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/when-was-the-first-general-election-held-in-india-1717473065-1

3. https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2024/May/22/the-steward-of-indias-first-date-with-democracy

4. https://testbook.com/question-answer/launched-in-1951-indias-first-five-year-plan–6230c47c9678fdf0e4ae23d4

5. https://www.drishtiias.com/to-the-points/paper3/five-year-plans

6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five-Year_Plans_of_India

7. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bharatiya_Jana_Sangh

8. https://www.indiavotes.com/pc/party_list/0/1

9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40209795

10. https://indianexpress.com/article/research/illiterate-voters-spread-of-communism-and-a-staggering-success-how-the-world-saw-the-first-indian-elections-9268746/

11. https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2024/Apr/29/rise-fall-of-small-parties