From Seeds of Division to Freedom at Midnight

Recap: The Midnight of Freedom: Independence, Partition & the Shaping of Modern India

In the first blog of the “India After 1947” series, we explored the critical events that set the stage for India’s independence and partition. The aftermath of World War II left Britain weakened and eager to exit India, while internal unrest, like the Royal Indian Naval Mutiny of 1946, signaled the end of colonial control. The 1946 provincial elections revealed the deep political divide, with the Congress and Muslim League drawing clear boundaries that made partition seem inevitable.

We also examined the rapid and often chaotic process driven by Lord Mountbatten and the drawing of the Radcliffe Line, which cleaved Punjab and Bengal, triggering the largest forced migration in history. Amidst this upheaval, the complex challenge of integrating 565 princely states loomed large—a task taken on by leaders like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V.P. Menon, whose diplomatic and strategic efforts shaped the emerging Indian Union.

This blog laid bare the intersection of political will, communal tensions, and urgent diplomacy that ignited the midnight moment of freedom—a triumph shadowed by tragedy.

Introduction

Even after 78 years, the story of India’s partition still starts arguments — not just in history classes but in living rooms across India and Pakistan. Many people wonder: Was the real villain of partition Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, or Muhammad Ali Jinnah? Historians and families keep discussing who was truly responsible and why things turned out the way they did.

The truth is, partition wasn’t just one big event on one evening. The story of separation began long before 1947. Its roots go four or five decades deep, shaped by leaders, political moves, and decisions that set the stage for one of history’s greatest migrations and tragedies.

Early Years — Jinnah’s Journey (1876–1906)

Let’s begin with Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Born in 1876 in Karahadar, Karachi, Jinnah came from a family that had moved from Hinduism to Islam a generation before. As a young man, Jinnah went to London to study law, then returned to India in 1896 to become a well-known lawyer in Bombay. For years, he was more interested in the law than politics. He believed in secularism and working together.

At first, Jinnah was not interested in religious politics. He was influenced by British law and wanted India’s independence to be won through dialogue and careful negotiation, not community division.

First Cracks — Partition of Bengal (1905) and Divide and Rule

Back in the early 1900s, Bengal became the center of revolutionary activity against British rule. The British, noticing this, decided to split Bengal into East and West in 1905. Lord Curzon, the Viceroy then, said this was to make administration easier, but many saw it as a clear move to divide people by religion: East Bengal was mostly Muslim, and West Bengal was mostly Hindu.

Indians did not like this move. The Indian National Congress (INC) protested peacefully, arguing for religious unity and an end to divide-and-rule. Muslim leaders, however, felt this move would help them get more political power, now that Muslims were the majority in East Bengal.

Muslim Representation and the Birth of the All India Muslim League (1906)

In 1906, a group of Muslims gathered in Dhaka, to talk about their political future. This meeting led to the formation of the All India Muslim League (AIML). The League wanted Muslim issues to get attention, and soon asked the British for “separate electorates,” meaning Muslims would vote only for Muslim representatives in special constituencies.

The British government supported this, seeing it as a way to keep Indians divided and easier to rule. In 1909, the Morley-Minto Reforms made separate electorates law. This was a big turning point; from now on, politics became more about communities rather than issues or ideas.

Jinnah’s Dual Role, and the Lucknow Pact (1913–1916)

Jinnah joined the Muslim League in 1913, while also staying a member of the Congress. He tried hard to keep Hindus and Muslims together. In 1916, he helped create the Lucknow Pact, where Congress and the Muslim League agreed to cooperate against the British and accepted some Muslim demands, including separate electorates and reserved Muslim seats in Bengal and Punjab. Sarojini Naidu at this time also called Muhammad Ali Jinnah as the ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity.

Not everyone liked this. Leaders like Lala Lajpat Rai and Madan Mohan Malviya disagreed and formed the Hindu Mahasabha in 1915. The political field kept getting more crowded and divided.

This was also the time when Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned from South Africa to join Indian politics — a name that would soon reshape the country’s freedom struggle.

Rising Tensions and Changing Leaders (1919–1925)

By 1919, Gandhi became the main leader in Congress. World events also touched India. After World War I, the Ottoman Empire collapsed. Many Muslims across the world, including India, worried about the future of their religious leader, the Caliph. The Khilafat Movement started, led by the Ali Brothers, asking Britain to protect the Ottoman Caliphate.

Gandhi, trying to keep Hindus and Muslims united, supported the Khilafat Movement. But Jinnah opposed mixing religion with politics and eventually left both the Congress and the Muslim League, feeling out of place during this period.

During the 1920s, the British passed laws that increased religious division, like the Punjab Municipal Amendment Act of 1923, which increased Muslim seats and reduced Hindu seats. Hindu leaders like Veer Savarkar spoke about making India a Hindu nation, and the British government banned his controversial book “Who is a Hindu?” In this climate, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was born in 1925, adding to voices calling for Hindu interests.

As the years passed, these divisions became sharper. The Congress talked of a united India. RSS and Hindu Mahasabha spoke for Hindus, and the Muslim League kept gaining ground among Muslims feeling left out by both sides.

The 1930s — Building to a Breaking Point

In 1930, the All India Muslim League, meeting in Allahabad, set out its dream for a separate Muslim-majority state in northwestern India. By the early 1930s, the word “Pakistan” (meaning “Land of the Pure”) began to appear.

Jinnah came back to India in 1934. This time, he was changed — no longer the ambassador for unity, he was now the voice for Muslims wanting their own nation. He made the League stronger, kept top leadership Muslim, and argued that Muslims and Hindus needed different countries. This was the time when the two-nation theory became the Muslim League’s clear message.

The British saw these divisions as useful for their own purposes. In 1935, they introduced the Government of India Act, making more people eligible to vote, which meant upcoming elections would be critical for all parties.

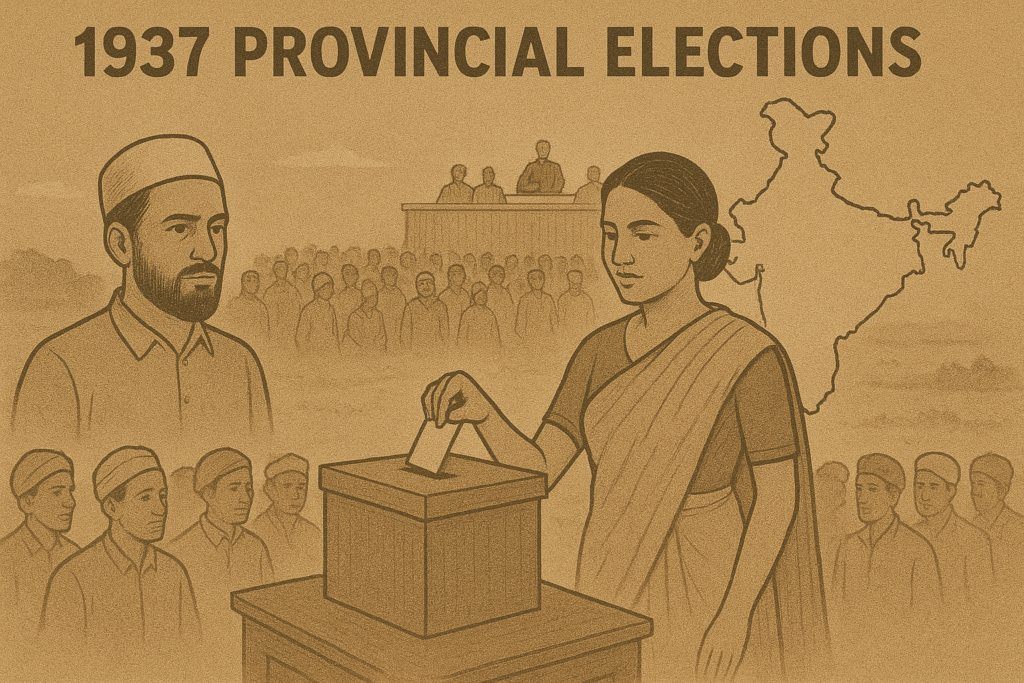

The Pivotal Elections of 1937

In the 1937 provincial elections, the Congress won a huge victory, getting 707 out of 1585 seats, while the Muslim League won just 106 seats. In some Muslim-reserved seats, Congress put up Muslim candidates and won, showing that many Muslims did not automatically side with the League.

The League realized its political weakness and started pushing the idea that only the League really represented Muslims. They also said Congress was a Hindu party, out to take away Muslim rights.

World War II and Shifting Loyalties (1939–1945)

In 1939, Britain declared that India would join World War II, without asking Indian leaders for their agreement. This deeply angered Congress. Under Nehru and Gandhi, Congress demanded a promise of full independence in exchange for support, but Britain refused.

The Congress party reacted by resigning from provincial governments and launching protests. They demanded “Purn Swaraj” (complete independence). Gandhi began the Quit India Movement in 1942, urging the British to leave immediately. The British responded by jailing Congress leaders, leaving a vacuum in Indian politics.

The Muslim League saw an opportunity. While Congress was protesting, Jinnah led the League to support the British war effort, hoping for rewards after the war. At the same time, the Hindu Mahasabha also supported the British, arguing that if the Muslim League did not resign from assemblies, why should they? With Congress leaders still in jail, the League and Mahasabha spread their own messages, and communal riots increased.

From 1939 to 1945, these three parties — Congress, the Muslim League, and the Hindu Mahasabha — followed different strategies that would shape India’s future. Congress fought for independence at any cost; the Muslim League focused on Muslim rights and the possibility of a separate country; Hindu Mahasabha pushed for Hindu interests and opposed Congress’s version of unity.

By 1945, the world had changed after the war. Britain was weakened and could not hold its empire much longer. Independence for India — and the question of one or two (or more) countries — moved to the center of every conversation.

India’s Population Map in 1947

When talking about 1947, it’s important to know who lived where. India had about 390 million people: around 65% were Hindus, and 27% were Muslims. But in some areas, the numbers were very different:

- Punjab: 57% Muslim

- Bengal: 55% Muslim

- Sindh: 71% Muslim

- Balochistan: 87% Muslim

- North-West Frontier Province (now in Pakistan): 94% Muslim

These differences made it even harder to keep a united country. Some regions were almost completely one community, while others were mixed. This would have big consequences when politicians started drawing lines on the map.

The Cabinet Mission Plan (1946)

Facing growing pressure, Britain decided to speed up decolonization. Three British cabinet ministers — Lord Pethick-Lawrence, Sir Stafford Cripps, and A.V. Alexander — were sent to India in March 1946. Their job was to find an agreement that could keep India united while ensuring rights for all communities. This became known as the Cabinet Mission Plan.

The plan suggested a united India with a weak central government. India would be divided into three groups of provinces:

- Group A: Hindu-majority areas (United Provinces, Central Provinces, Bombay, Madras, Bihar, Odisha)

- Group B: Muslim-majority areas in the Northwest (Punjab, Sindh, North-West Frontier Province, Balochistan)

- Group C: Bengal and Assam

Each group would have its own local government, and the central government would only look after defense, foreign affairs, communication, and finance. Princely states could choose whether to join any group or stay independent.

After five years, provinces were free to change their group or leave. The plan aimed for cooperation and avoided full partition. For a moment, both Congress and the League seemed willing to try it. Jinnah thought it might allow for a bigger Muslim-majority area in the future, while Congress wanted more power at the center and reorganization by letting elected members decide which group to join.

But soon disagreement returned. Congress wanted freedom to reorganize provinces and didn’t trust the weak center; the Muslim League feared Congress would dominate the new structure. The talks failed again.

The Elections of 1946 and Direct Action Day

In provincial elections held right after, Congress won 923 of the 1585 seats while the Muslim League won 425 seats out of only 482 it contested — especially in Muslim-majority constituencies, often with more than 90% of the vote in some places. This made it clear: Congress led Hindu India, the League clearly led Muslim India.

With no agreement in sight, Jinnah announced a “Direct Action Day” on August 16, 1946 — a day of protest to show Muslim demands couldn’t be ignored. What happened next was a tragedy: huge riots broke out in Calcutta (known as the “Great Calcutta Killing”), and violence quickly spread across the country. Thousands died, and communities became even more divided.

British Decision and Clement Attlee’s Role

In Britain, the Labour Party won the 1945 election, and Clement Attlee became Prime Minister. Unlike Churchill, Attlee was determined to end colonial rule. On 20 February 1947, Attlee made a historic announcement in the British Parliament: Britain would leave India by June 1948, no matter what happened with negotiations between Indian parties.

This speech changed everything. Both Congress and the Muslim League understood time was running out. For the Congress, this meant having to finally accept partition to avoid chaos. For the League, it meant a separate Pakistan was now within reach.

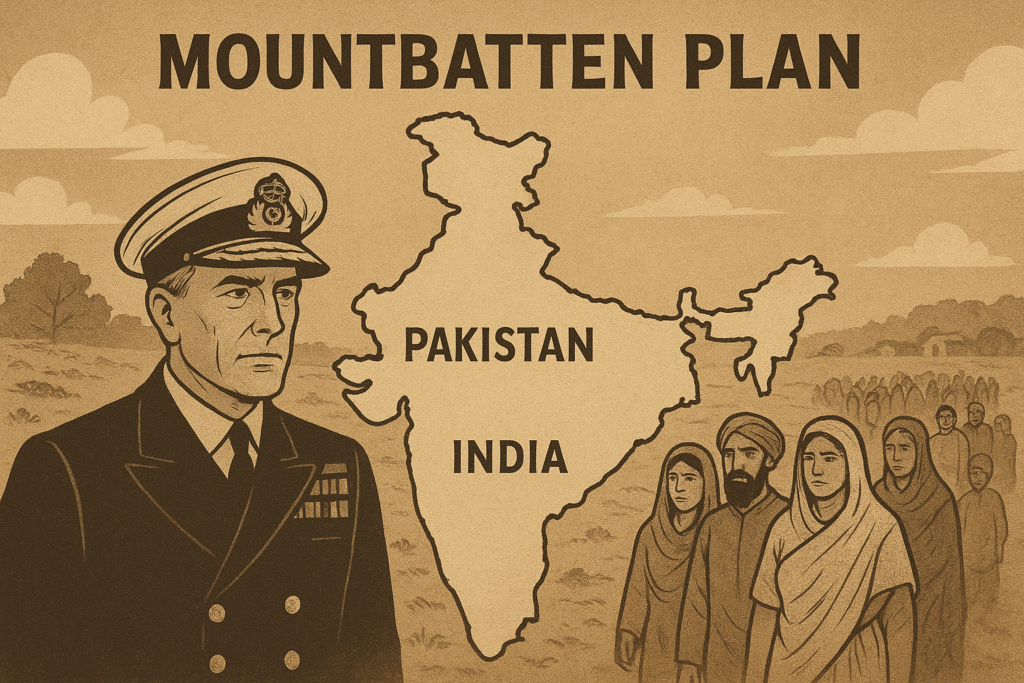

Faced with unrest, Britain sent a new Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, with direct orders to transfer power quickly. Both Nehru and Jinnah started preparing for partition.

The Mountbatten Plan and the Countdown to Partition

Mountbatten’s plan was simple: divide British India into two countries — India and Pakistan. Punjab and Bengal would be split after votes in their assemblies; the Sikh and Hindu communities in these regions voted to stay with India, but most of these provinces’ areas became Pakistan. Resources, government offices, and the military would also be divided.

To fix the new borders, a British lawyer, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, was called to draw the lines. Radcliffe had never been to India before, and he was given only 3–5 weeks to do the job. The result was confusion and unfairness — many important towns and temples ended up in the wrong country. And the new borders were not revealed to the public until two days after independence, causing even more confusion and violence.

The date for independence was moved up to 15th August 1947. Pakistan would declare independence on the 14th, and India on the 15th.

Midnight’s Freedom and Its Pain

On the night of 14th/15th August 1947, India and Pakistan were born as two separate countries. Lord Mountbatten became the first Governor-General of India, while Jinnah made himself Governor-General of Pakistan.

The actual boundary line was made public on 17th August, after two countries had already celebrated independence. This delay led to panic. Around 14 million people, Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs, crossed hurriedly drawn borders, leaving behind homes, friends, and lives. At least one million people died. There was violence, many women were attacked or kidnapped, and a deep sense of loss spread through families on both sides.

Finally, on 26th January 1950, India became a full republic, ending its constitutional link with the Crown.

Conclusion: The Real Lesson

The history of partition is not just about borders or leaders. It is about people — about lives changed forever by political decisions, ambitions, and, above all, by failures to compromise. Partition was the result of decades of mistrust, policy, and political rivalry, not just one day or a single meeting.

78 years later, memories may fade, but this lesson remains: as long as we keep talking, wondering, and debating, perhaps the full story of India’s partition will keep teaching future generations the high cost of division.

Looking Ahead:

This concludes Blog 1.2. In Blog 1.3: Integrating the Princely States: Junagadh & Hyderabad, we will see how India tackled the huge challenge of persuading and integrating hundreds of princely states into the Union — with remarkable stories of Junagadh and Hyderabad.

References (Books):

1. The Story of the Integration of the Indian States– V.P. Menon (1956)

2. The Transfer of Power in India – V.P. Menon (1957)

3. Freedom at Midnight — Dominique Lapierre & Larry Collins (1975)

4. The Discovery of India — Jawaharlal Nehru (1946)

5. The Transfer of Power 1942–47 (12 Volumes) — Edited by Nicholas Mansergh

6. Patel: A Life – Rajmohan Gandhi (1990)

7. India After Gandhi – Ramachandra Guha (2007)

References (TV Shows/Movies):

1. Pradhanmantri TV Series- ABP News (2013)

2. Freedom at Midnight- Sony Entertainment Television (2024)

References (Web Pages):

1.https://www.britannica.com/topic/East-India-Company#.

2.https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/british-east-india-company#:~:text=the%20East%20India%20Company%20had%20small%20beginnings.

3.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wazir_Mansion#/media/File:PK_Karachi_asv2020-02_img28_Wazir_Mansion.jpg

4.https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah#:~:text=Jinnah%20was%20the,October%2020%2C%201875.

5.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah#/media/File:Lincolns_Inn_1.jpg

6.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah#/media/File:JinnahBarrister.jpg

7.https://www.indianrajputs.com/i/british_india_map.png

8.https://ncert.nic.in/textbook/pdf/lehs305.pdf